Foster Ohio History: From Presidential Trains to Sam the Chimp | Warren County Real Estate

A Deep Dive into Foster, Ohio: The Rise and Fall of a Little Miami River Community

A forgotten village that witnessed presidential trains, powered by governors’ mills, and bridged the gap between Ohio’s frontier past and industrial future

The Setting: Where Waters Meet History

Nestled in the rolling hills of Warren County, Ohio, where Hamilton and Deerfield Townships converge along the winding banks of the Little Miami River, once stood a thriving community that few remember today. Foster, Ohio—sometimes called Foster’s Crossing or simply Fosters—represents a quintessential story of 19th-century American settlement: rapid growth, bustling commerce, and eventual decline as transportation patterns shifted and progress bypassed small river towns.

The community sat at a strategic crossroads where the Old Three C Highway (connecting Cincinnati, Columbus, and Cleveland), the Fosters-Maineville Road, the Socialville-Fosters Road, and the Davis Road all converged. More importantly, it straddled the historic Little Miami Railroad, making it a vital link in Ohio’s early transportation network.

The Foster Family Legacy: Building an Empire at the River’s Edge

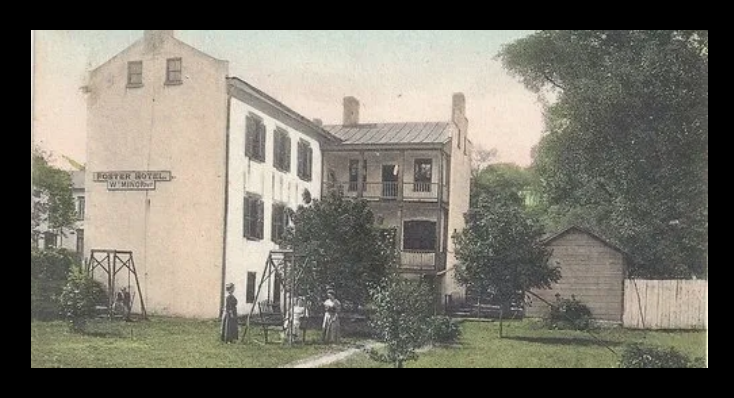

The town’s story begins with James H. Foster, who came to the area in 1841 or 1842 and built a mill and hotel on the east side of the river. His hotel, strategically named “22 Mile Stand,” marked its location exactly 22 miles from Cincinnati, making it a crucial waystation for travelers on the bustling route between Ohio’s emerging cities.

James Foster wasn’t just a businessman—he was considered the leading merchant of the town until his retirement in 1865. His enterprise established Foster’s Crossing as more than just a river ford; it became a legitimate commercial center that would attract settlers, businesses, and even presidential attention.

James Foster wasn’t just a businessman—he was considered the leading merchant of the town until his retirement in 1865. His enterprise established Foster’s Crossing as more than just a river ford; it became a legitimate commercial center that would attract settlers, businesses, and even presidential attention.

A Presidential Moment: Lincoln’s Historic Passage

One of Foster’s most remarkable moments came during the tumultuous period preceding the Civil War. On February 13, 1861, the presidential train of Abraham Lincoln passed through the town on its way to Columbus from Cincinnati, traveling on the historic Little Miami Railroad. This event marked Foster as a witness to one of American history’s most critical transitions, as Lincoln made his way to Washington for his inaugural.

The timing was particularly significant—this was Lincoln’s famous pre-inaugural journey, during which he addressed crowds and attempted to calm a nation sliding toward civil war. For the residents of Foster, seeing the future president’s train thunder through their small community must have been both thrilling and sobering.

The Governor’s Mill: Jeremiah Morrow’s Industrial Vision

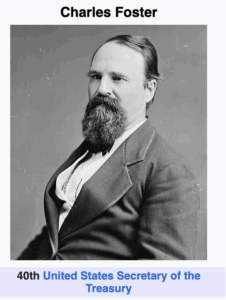

Perhaps no single figure was more important to Foster’s development than Jeremiah Morrow, Ohio’s ninth governor (1822-1826), who operated a crucial gristmill in the community. His gristmill was one of the foremost mills in the territory, and after retiring from politics, he returned to his farm and gristmill in Warren County until his death in 1852.

Perhaps no single figure was more important to Foster’s development than Jeremiah Morrow, Ohio’s ninth governor (1822-1826), who operated a crucial gristmill in the community. His gristmill was one of the foremost mills in the territory, and after retiring from politics, he returned to his farm and gristmill in Warren County until his death in 1852.

Morrow’s connection to Foster represented more than just business—it symbolized the intersection of political power and economic development in frontier Ohio. As the first president of the Little Miami Railroad from 1837 to 1845, Morrow had direct influence over the transportation infrastructure that made Foster’s prosperity possible.

The mill operation passed through several hands but remained central to Foster’s economy. Augustus Hoppe purchased the Foster Mill from Seth Greely in 1886, and the milling enterprise became a fruitful family business until January 1944, when a mill accident took the life of Edward Augustus Hoppe.

A Bustling Commercial Center: Foster in Its Prime

By 1868, Foster had evolved into a remarkably diverse and active commercial center. An early history written in 1868 reported that forty-seven houses were grouped together at corners on both sides of the river, with twenty-seven consisting of business houses and shops.

The commercial district was impressively comprehensive for such a small community:

- Retail establishments: Three dry goods and grocery stores

- Specialized services: A merchant tailoring house, two boot and shoe establishments

- Hospitality: A first-class boarding house

- Industrial operations: A grain depot, flouring mill, sawmill, and distillery

- Transportation hubs: Railroad depot with express offices, post office, telegraph office, and ticket office

- Trades: A cooper shop and blacksmith shop

- Recreation: Five beer saloons (though the chronicler noted wryly that “of these saloons we have just five too many”)

- Infrastructure: A tollgate house for the turnpike

This commercial diversity reveals Foster as a genuine regional center rather than merely a railroad stop. The presence of specialized craftsmen, multiple retail options, and comprehensive transportation services indicates a community that served a substantial rural hinterland.

A Melting Pot Community

Foster’s population in 1868 totaled 180 people, but what made it remarkable was its diversity. One hundred and five were German, fifty were American, and twenty-five were Irish. This demographic composition reflected broader immigration patterns in Ohio, where German immigrants often settled in small towns and established businesses.

The German community was particularly influential. The German residents were described as “an industrious and business type group” where most owned real estate and acquired comfortable homes with a few acres of ground. The community even supported two day schools—one German and one American, with ladies of the village teaching each.

Entertainment and Social Life: Hoppe’s Island Paradise

Foster’s social heart centered around an unusual geographical feature created by industrial activity. A gristmill on the river cut off about an acre of ground, forming an island that incorporated three residential homes and a sawmill. This island, initially used for practical purposes like framing covered bridge timbers, eventually became “Hoppe’s Island,” a get-away paradise in the 1920s and ’30s where families from near and far frequented for entertainment and relaxation.

The island offered comprehensive recreation: swimming, canoeing, picnicking, dancing, or perhaps just the place for a family gathering. Its popularity was extraordinary—on Sundays it was impossible for visitors to reserve a picnic table unless at the premises as early as 5 a.m.

Cultural entertainment flourished alongside outdoor recreation. The community boasted “Liberty House,” built by M. Obergefell, a German immigrant and merchant tailor who arrived from Cincinnati in 1865. The building later became Maag’s Hall, which continued hosting dances until about 1930, featuring mainly quadrilles with German-type bands and fiddlers performing.

The Blue Danube Tavern: Foster’s Social Institution

Long before the turn of the century, the Blue Danube Tavern was a fashionable three-story hotel and restaurant that served as Foster’s premier social institution. Theresa Englert operated the building as a summer resort from 1892 to 1907, catering to visitors seeking respite along the Little Miami River.

The building survived multiple challenges, including the flood of 1913, when a big log reportedly washed downstream and knocked out one end of the building. Despite damage and changing ownership, it maintained its identity as the Blue Danube Tavern until 1975, when it was completely remodeled and became “The Train Stop Inn.”

Interestingly, the tavern developed a somewhat notorious reputation in its later years. One former deputy sheriff recalled: “As I remember it, Foster was a thriving little town, full of all kinds of fights and shootings. We never had many calls to the Blue Danube, but when we did, it was a good one.”

The Mill That Built a Community: Industrial Innovation

The economic foundation of Foster rested on its milling operations, which represented cutting-edge technology and market connections. The mill produced cake flour from soft winter wheat and supplied Lebanon and Cincinnati bakeries until its shutdown. The operation was renowned for quality—it was said to have used fine silk cloth to sift the flour so that in the end it was truly “as fine as silk”.

Beyond wheat flour, the mill diversified its products: it also produced and distributed pancake flour and cornmeal, with “Pride of Miami” as the mill’s top brand. The operation served both commercial and individual customers, doing custom grinding for families who brought in their wheat, corn, rye, barley and other grains used primarily for hog feed, as Warren County was one of the major suppliers of processed pork in early times.

The Postal Service Evolution: A Community’s Identity Crisis

Foster’s struggle with its postal identity reflects broader challenges faced by small Ohio communities. The post office name changed multiple times, creating confusion that persisted for over a century:

- Foster’s Crossings (October 27, 1859 – August 28, 1883)

- Foster (August 28, 1883 – January 7, 1884)

- Foster’s (January 7, 1884 – June 6, 1893)

- Foster (June 7, 1893 – June 30, 1961)

- Maineville (July 1, 1961 – present)

An article from 1989 noted: “The citizens of Foster’s still couldn’t decide on a proper spelling of the name of their post office”, highlighting the community’s ongoing identity challenges even as it declined.

The Bridge That Changed Everything: Progress as Destroyer

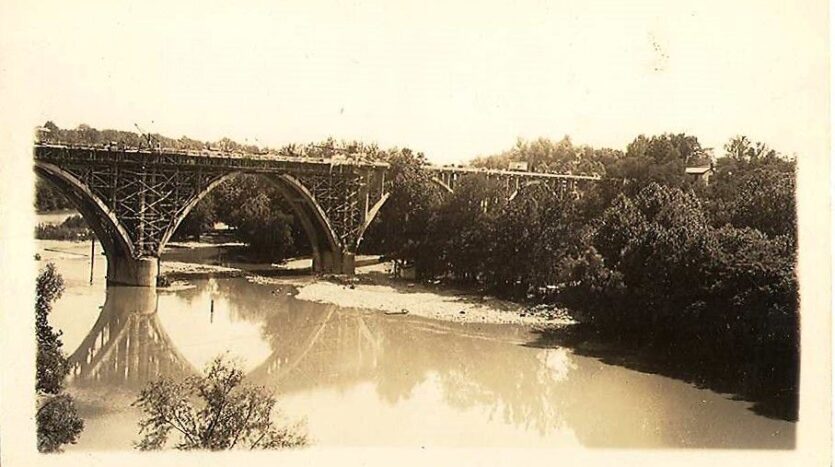

Foster’s decline began with what should have been progress. The viaduct was started in October 1936 and completed October 1, 1938, at a cost of half a million dollars, taking over 90,000 man-hours to complete. This massive engineering project used approximately 9,000 cubic yards of concrete and 1,200,000 pounds of reinforcing steel.

The bridge was an impressive achievement: six spans varying in length from 155 to 175 feet supported the viaduct, with the deepest concrete pier anchored 27 feet below water level. At the center pier, the roadway stood slightly over 75 feet above the Little Miami River.

However, this engineering marvel proved devastating to Foster’s economy. Travelers in stagecoach days had crossed the river when traveling the old Montgomery, Hopkinsville and Wilmington Pike, but they could not have envisioned that the progress of Foster would be put on the back burner because of the huge viaduct that would span the Little Miami many years later.

The new bridge allowed traffic to bypass Foster entirely, eliminating the community’s role as a necessary stop for travelers. What had been Foster’s greatest advantage—its position as a river crossing—became irrelevant overnight.

Archaeological Connections: Ancient Roots

Foster’s history extends far beyond European settlement. Fosters Earthworks, located on a wooded hilltop site on the west side of the river, was investigated in 1890 by archaeologist Frederick Ward Putnam, who called it “a singular ancient work” of the Hopewell culture.

This archaeological connection reminds us that Foster’s strategic location along the Little Miami River had attracted human settlement for over a millennium before James Foster built his mill and hotel.

Decline and Memory: The Fate of Small-Town America

Foster’s story represents thousands of similar communities across the Midwest that thrived in the 19th century but couldn’t adapt to 20th-century transportation changes. The last few years saw a gradual decline in the once-prosperous village. As the older citizens moved on, it left a vacancy that could not be filled as in olden days.

Today, Foster exists more as a geographical reference than a community. The mill foundation and portions of the millrace still survive, and the Little Miami Bike Trail passes through the area, allowing cyclists and hikers to experience the natural beauty that first attracted settlers to this bend in the river.

Legacy: What Foster Teaches Us

Foster, Ohio’s rise and fall illuminates several crucial themes in American development:

The Power of Transportation: Foster’s prosperity depended entirely on its position along transportation routes. When those routes changed, the community couldn’t survive.

Immigration and Integration: The German-American community in Foster demonstrates how ethnic diversity strengthened small towns, bringing skills, capital, and cultural richness.

Industrial Innovation: From Jeremiah Morrow’s territorial mill to the Hoppe family’s specialized flour operation, Foster shows how technological advancement and market connections sustained rural communities.

Environmental Interaction: Foster’s residents worked with natural features—the river, the island, the crossing—rather than simply imposing development upon the landscape.

Political and Economic Intersection: Governor Morrow’s mill demonstrates how political figures directly participated in local economic development, understanding that prosperity required both vision and investment.

The Double Edge of Progress: The viaduct that bypassed Foster reminds us that infrastructure improvements often create winners and losers, sometimes destroying the communities they were meant to help.

Foster, Ohio may be largely forgotten today, but its story encapsulates the dreams, achievements, and ultimate vulnerability of small-town America. In its mills and taverns, its diverse population and presidential visits, its island paradise and commercial bustle, we see reflected the broader story of a nation transforming from frontier to industrial power—and the human communities caught in that enormous transition.

Modern Day Foster: The Monkey Bar and Grille Era

While historic Foster may have faded as a commercial center, the community found new life in an unexpected form—as home to one of Ohio’s most famous (and infamous) establishments, the Monkey Bar and Grille.

The Train Stop Inn Transformation

The old Blue Danube Tavern, which had survived floods, ownership changes, and decades of decline, underwent a remarkable transformation. By the 1970s, it had become the Train Stop Inn, catering to local motorcycle clubs and residents. Foster remained a small river town, off the beaten path, where everyone knew each other, believed in the right of privacy, lent a hand when needed, but respected and expected self-reliance. The Blue Danube, now named the Train Stop Inn, catered to the local motorcycle clubs and other locals.

Sam the Chimp: Foster’s Most Famous Resident

In 1985, Foster gained national notoriety when Ken Harris, owner of the Train Stop Inn, acquired a chimpanzee named Sam. In 1985 the Bar’s owner, Ken Harris, adopted a young chimpanzee named Sam, who quickly became a local celebrity. He was often seen interacting with patrons, smoking a cigarette, drinking a grape soda and adding a lively and exotic flair to the establishment.

In 1985, Foster gained national notoriety when Ken Harris, owner of the Train Stop Inn, acquired a chimpanzee named Sam. In 1985 the Bar’s owner, Ken Harris, adopted a young chimpanzee named Sam, who quickly became a local celebrity. He was often seen interacting with patrons, smoking a cigarette, drinking a grape soda and adding a lively and exotic flair to the establishment.

Sam’s origin story varies depending on who tells it. “Kenny always told me he won Sam in a poker game,” while other stories say that Sam was first owned by a local individual who rented canoes, and came to Ken after Sam bit the owner’s hand. Most of the stories agree that Sam and another chimpanzee, named Rudy, originated from a carnival that went bankrupt and was abandoned in Boone County Kentucky.

Sam quickly became a regional celebrity, living in an abandoned foundation that was turned into living quarters for Sam in front of the tavern. During Sam’s time at the Train Stop Inn, many fond memories were created.  Most of the stories revolve around memories of Sam smoking and drinking beer or grape soda, although he loved Snickers and Coffee, as well.

Most of the stories revolve around memories of Sam smoking and drinking beer or grape soda, although he loved Snickers and Coffee, as well.

The Sam the Chimp Trial: National Attention

Sam’s unusual lifestyle eventually caught the attention of animal rights activists. Around the time that Little Miami Scenic Trail was finished and gaining popularity, the US Humane Society caught wind of a chimpanzee along the bike trail. Although there were many happy stories involving Sam, some did not feel his living conditions were appropriate for a chimp. On April 15, 1987, Sam was confiscated and taken to temporary quarters at Ohio State University.

The case became a cause célèbre, attracting national attention. Harris’ court case attracted lots of attention, with some clamoring for Sam to return to his devilish lifestyle and animal rights activists demanding the chimp be released from his racy conditions. The trial even caught the attention of renowned primatologist Jane Goodall. The trial even captured the attention of Jane Goodall, world-renowned primate expert and researcher. She wrote an excerpt in her book, she co-authored with Dale Peterson. The book is titled, “Visions of Caliban on Chimpanzees and People.” Patrons of the former Train Stop Inn say they heard Jane Goodall say that Sam was the happiest chimp she had ever seen.

Support for Harris and Sam was overwhelming in the local community. Support swelled for Harris as “word got out that the chimp missed his cigarettes, his booze and his sex life.” Petitions for Sam’s return to paradise attracted thousands of signatures.

In the end, the jury decided to acquit Ken Harris of cruelty to animals and Sam was returned to his living quarters. However, Sam’s final fate remains a mystery to this day, Some believe he was sent to an animal reserve in Florida, but it remains a mystery today.

The Modern Monkey Bar and Grille

Today’s Monkey Bar and Grille represents Foster’s successful reinvention as a recreational destination. What was once a humble railroad, a bustling hotel, and even a monkey-hosted biker bar (yes, you read that right – an actual Monkey!) is now a welcoming, family friendly establishment that sits on the Little Miami River.

The establishment has evolved into a multi-faceted destination featuring several distinct areas:

The Patio Bar: The most lively of the bars – located right next to the outdoor patio that sits on the Little Miami River. Enjoy the scenic views and live music 7 days a week during the Summer months.

The Lincoln Bar: Pays homage to the visit of a legend, Abraham Lincoln himself during its days as a hotel. Patrons can feel transported through time while enjoying a drink on the penny lined bar – a sight to see for yourself.

Little Miami Bike Trail Connection

The establishment has found new purpose as a key stop along the Little Miami Bike Trail. It is located right on the Little Miami Bike Trail with views of the Little Miami River. Start your bike ride at The Monkey Bar and end it with a drink on the patio bar or take the family for lunch and enjoy a scenic walk afterward. There’s even a spot to park your kayak if you are coming from the river!

Reviews consistently praise the location and atmosphere: “We rode the Little Miami Trail from Morrow to The Monkey Bar and Grille. They have a great selection of beer and drinks, two food trucks were set up in the lot. The service was quick on a Sunday afternoon. We absolutely loved the atmosphere and the music performer was awesome”.

Recent Challenges and Community Support

The establishment faced a significant setback in 2023 when a kitchen fire around 12:30 a.m. on May 3 caused heavy damage, with crews met with heavy flames coming from the kitchen. “All of the fire damage was contained to the kitchen area. The kitchen is a complete loss and then there is water and smoke damage throughout the rest of the building,” said Hamilton Township Fire Chief Jason Jewett.

The establishment faced a significant setback in 2023 when a kitchen fire around 12:30 a.m. on May 3 caused heavy damage, with crews met with heavy flames coming from the kitchen. “All of the fire damage was contained to the kitchen area. The kitchen is a complete loss and then there is water and smoke damage throughout the rest of the building,” said Hamilton Township Fire Chief Jason Jewett.

The community response was remarkable. All Monkey Bar and Grille employees can enjoy a free meal and a cold beer at Cartridge Brewing every day through the end of May. “Our hearts go out to our partners on the trail, and we want to do our part to help,” a spokesperson for the brewery said. Other local businesses, including Montgomery Inn, Firehouse Grill, and Mac’s Pizza, also offered support.

The restaurant successfully reopened just one month after the fire on June 3, 2023, with the announcement: “After 30 days of hard work and dedication since the fire, we are thrilled to welcome our community back into the bar”.

Community Traditions and Modern Amenities

Today’s Monkey Bar maintains connections to its colorful past while serving modern needs:

- On weekends, patrons can Meet Mel, the keeper of the tales and memories. On Saturdays, she shares stories and photos of her youth working at the Monkey Bar with Sam the Chimp

- On Sunday mornings, the Monkey Bar transforms into “Church at the Bar”, where the operations manager doubles as a pastor, welcoming all to come together and find solace and community

- After the tragic kitchen fire in 2023, The Monkey Bar decided to incorporate an outdoor container kitchen to keep their patron’s bellies full

- The Monkey Bar likes to give back. Join their latest initiative, “Change for a Dollar,” as they partner with Joshua’s Place to combat hunger in the Mason/Kings School District

Foster’s Archaeological Heritage

Modern Foster also preserves its deeper past. Fosters Earthworks (private property) is located on a wooded hilltop site on the west side of the river across from the Monkey Bar and Grille. In 1890, archaeologist Frederick Ward Putnam investigated here. He called it “a singular ancient work” of the Hopewell culture, because he found that the walls were loaded with heavily burned stone, earth, and clay.

Legacy: From Presidential Trains to Viral TikToks

In 2024, the tale of Sam the Chimp was unearthed in a viral TikTok, bringing new attention to Foster’s unique place in American popular culture. The story demonstrates how this small river community has consistently found itself at the intersection of transportation, entertainment, and national attention—from Lincoln’s presidential train in 1861 to Sam’s courtroom drama in 1987 to social media virality in 2024.

Foster’s evolution from frontier crossing to industrial center to recreational destination illustrates the adaptability required for small communities to survive changing times. While the mills may be gone and the commercial bustle a memory, Foster has found new life as a place where cyclists pause, kayakers rest, and families gather along the same river bend that attracted James Foster nearly two centuries ago.

About This Series: Preserving Ohio’s Hidden Stories

This deep dive into Foster’s remarkable history is brought to you by Pam Socha, Realtor®, whose passion for Ohio’s rich heritage drives her to uncover and share the fascinating stories behind our communities. As someone who has spent years helping families find their perfect homes throughout Warren County and beyond, Pam understands that every neighborhood, every street, and every property has a story to tell.

“When you truly know the history of a place, you develop a deeper connection to it,” says Pam. “Foster’s story—from presidential trains to famous chimps—reminds us that even the smallest communities can have the most extraordinary tales. This is what makes Ohio real estate so special—you’re not just buying a home, you’re becoming part of a living story.”

Pam’s commitment to preserving local history stems from her conviction that understanding our past enables us to make more informed decisions about our future. Whether you’re looking for a historic home with character, a modern family residence, or an investment property, knowing the stories behind the communities makes all the difference.

Watch for Pam’s next historical deep dive: Kings Island’s surprising connections to Warren County’s past—you won’t believe how this world-famous amusement park ties into the very communities we’ve been exploring!

Ready to Write Your Own Ohio Story?

Whether you’re drawn to historic river communities like Foster, vibrant suburban neighborhoods, or peaceful rural properties, Pam Socha is here to help you find the perfect place to call home. With her deep knowledge of local history and market expertise, she’ll help you discover not just a house, but a community with character.

Contact Pam Socha, Realtor® today:

- 📧 Email: sochasells@gmail.com

- 📱 Phone: 513-600-8844

- 🌐 Website: https://sochasells.com

- 📍 Serving Warren County, Hamilton County, and surrounding Ohio communities

“Let’s find you a home with a story worth telling!”

The remains of Foster’s foundations still rest along the Little Miami River, but today they’re joined by the laughter of families, the stories of Mel sharing Sam’s adventures, and the gentle splash of kayaks—silent testimony to a community that once thrived and, in its own unique way, thrives still where waters meet and history flows on.